You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘New Holland’ tag.

Tag Archive

The Wild Australian Children

December 31, 2010 in White Tribes | Tags: Allan Quatermain, Barnum, British Israelites, Ernest Favenc, Fate Magazine, George Firth, Great Zimbabwe, H. Rider Haggard, Israel, Jonathan Swift, Jungun, Lemuria, Literature, Lost Tribe, Melissa Bellanta, New Holland, P.T. Barnum, Rosa Praed, Secret of the Australian Desert, She, sideshows, W.J. Perry, White Tribe | Leave a comment

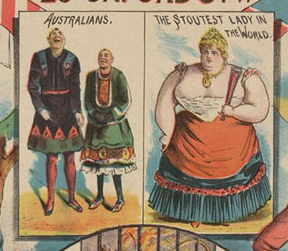

The Wild Australian Children, a sideshow act in the USA in the 1860s and 1870s, were recently brought to everyone’s attention by Melissa Bellanta on her excellent blog, Vapour Trails. In an interesting entry, Bellanta discussed her recent research on ‘Lost Race’ literature, which populated fin de siècle Australian literature, pointing to the influence of ideas concerning Lemuria, racial degeneration, and literary models from England (Rider Haggard’s She and Allan Quatermain, for example) as keys to this enthusiasm.

Her article suggested an interesting point concerning the potential influence of exhibits such as these ‘Wild Australian Children’ on this intriguing literary scene, which I think is worthy of being thought about a little more:

What I didn’t realise […] was that the idea of a lost race in the Australian interior had roots in a mid-nineteenth century freak show. Indeed, from about the mid-1860s, two unfortunate kiddies from Circleville, Ohio, were billed as ‘the Wild Australian Children’ in a travelling American exhibit of freaks and ‘scientific’ curios. In the cruel argot of the business, these children were ‘pinheads’: that is, they were microcephalic, and had severe intellectual disabilities. Promotional pamphlets accompanying their exhibit described them as the members of a near-extinct cannibal tribe, plucked from the desert wilds of Australia by an explorer-adventurer, Captain Reid. According to their publicity, “phrenologists and other scientific men” had come to the view that the Wild Australians ”belonged to a distinct race hitherto unknown to civilisation”.

But what about the case of the Wild Australian Children? Their influence, if one indeed existed, must be seen as altogether more diffuse. I know of no novel or story which describes the Lemurian races of Australia as mentally damaged or pinheaded; in line with the theosophical ideas of the time, and the diffusionist arguments of W.J. Perry, most of these races were fully formed, albeit often savage, humans, corrupted by the environment into cannibalism or broader savagery. In this manner the Wild Australian Children seem more like literary remnants of Swift than precursors of Haggard, Firth, Praed, Favenc and their ilk.

However, I suppose in the notion of being plucked from cannibalism by Capt. Reid is a touching point with more traditional lost tribe ideas which were popular during the late nineteenth century: even if such ideas relate merely to the inherent superiority of European civilization. It is worth pointing out, however, that the tales told about these particular microcephaloids did not restrict them altogether to the Austral continent. P.T. Barnum exhibited another set of pinheads, claiming they hailed from a forgotten remnant Aztec empire, or from far-east Asia: exotic places not many had visited, in other words. The notion that pinheads were ‘Australian’, however, seemed to maintain some currency. Brett, a reader of Bellanta’s blog, pointed out that a similar set of pinheads (in Balkan costume!?!?!) were displayed to London audiences in 1885.

Equally, there was and had been a pre-existing matrix of ideas about ‘white’ tribes which had been circulating for millennia. The Lost tribes of Israel had long been a bugbear in western consciousness, and when tribes of ‘white’ Indians were discovered in New England in the 1640s there were claims that they had Hebrew origins. Periodically they would reappear in various places. In nineteenth century Britain, speculation was rife concerning British Israelites and the distribution of other tribes of Israel, all of which suggested that whites could be found in other areas throughout the world, and ensured that the notion of ‘white tribes’, as well as their international distribution, were part of the general consciousness. Occasionally, rumours of tribes could be linked to entirely other discourses. In 1834, there was some speculation about a group of Dutch living in the hinterland of New Holland’s north coast, which was apparently product of a mass of interlocking notions of geographical discovery, pseudo-scientific conclusions about inland seas, and thus reflected little of the contemporary anxieties concerning race which seemed to infect contemporary discourses on white tribes.

Concerning Haggard’s Allan Quatermain and She, novels which Bellanta points to specifically as being potentially influenced by the Wild Australian Children, surely the contemporary debate about the white origins of the immense ruins of Great Zimbabwe must have played a role in his musings? A far greater one, perhaps, than a viewing of a pair of retarded microcephaloids at a London sideshow, one would imagine. It thus seems to me more likely to me that the Wild Australian Children, as well as the white tribes of She etc, are rather manifestations drawing on the same Zeitgeist, rather than successive iterations of a singular strand of influence, falling like dominos across the nineteenth century.

But all of this might be, in a way, demonstrative of Bellanta’s major point. Although difficult to substantiate, it remains entirely possible that this particular sideshow exhibit influenced some musings on the idea of lost Australian white tribes. We know little about the mechanics of influence of sideshow acts – their inherently ‘low’ (I use the term advisedly) status probably made them less likely to be acknowledged as influences on literary escapades of the nineteenth century.

As the case of Jungun (discussed in a previous post, and hopefully again in the near future) demonstrates, popular entertainments and sideshows could indeed exercise a remarkable, and largely invisible, impact on literary endeavours. As a case in point, although it seems clear to me that Jungun’s story was a major inspiration for Ernest Favenc’s The Secret of the Australian Desert (1895), this albino aboriginal was not mentioned at all in Favenc’s foreword, which outlined other sundry influences upon the text.

Those looking to own their own piece of ‘Wild Australian Childreniana’ (cough) should click here, and scroll down to item 25.